- Home

- Michael Pollan

Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation Page 4

Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation Read online

Page 4

In all the time I’ve now spent with pit masters, whiling away the hours before the smoldering logs, I’ve never once brought up Freud’s fire theory. I’m just not sure how well it would go over. I have, however, on occasion brought up a second theory, one that, though it is equally outlandish, contains a bright cinder of poetic truth that can usually be counted on to bring a smile to the streaked, perspiring face of a barbecue man.

This is the theory put forward by Charles Lamb, the English writer (1775–1834), in his essay, “A Dissertation upon Roast Pig.” Lamb claims that all meat was eaten raw until the art of roasting was accidentally discovered, in China, by a young man named Bo-bo, the dimwitted son of a swineherd named Ho-ti. One day, while Ho-ti was off gathering mast for his pigs, his son—“a great lubberly boy” who liked to play with fire—accidentally burned down his family’s cottage, in the process incinerating a litter of piglets. While he was surveying the ruins and deciding what to tell his father, “an odor assailed his nostrils, unlike any scent which he had before experienced.” When Bo-bo reached down to feel one of the burnt pigs for any sign of life, he singed his fingers and then instinctively touched them to his tongue.

“Some of the crumbs of the scorched skin had come away with his fingers, and for the first time in his life (in the world’s life indeed, for before him no man had known it) he tasted—crackling!”

Bo-bo’s father returned to find his cottage in ruins, his piglets dead, and his son gorging himself on their corpses. Ho-ti was sickened by the scene of carnage, until his son exclaimed to him “how nice the burnt pigs tasted,” and, bewitched by the extraordinary aroma, he, too, sampled a piece of crackling and found it irresistibly delicious. Father and son decided to keep their discovery secret from their neighbors, whose disapproval they feared; to burn one of god’s creatures was, after all, to imply it was less than perfect raw. But in time

Strange stories got about. It was observed that Ho-ti’s cottage was burnt down more frequently than ever. Nothing but fires from this time forward … As often as the sow farrowed, so sure was the house of Ho-ti to be in a blaze.

Their secret eventually got out, neighbors tried the technique for themselves and marveled at the results, and the practice caught on. In fact, the custom of burning down houses to improve the taste of piglets grew so widespread that people began to worry that the art and science of architecture would be lost to the world. (“People built slighter and slighter every day,” Lamb tells us, and “now there was nothing to be seen but fires in every direction.”) Fortunately, a wiser head eventually figured out that the flesh of pigs might be cooked “without the necessity of consuming a whole house to dress it.” The invention of the gridiron and then the spit soon followed. And so did humankind discover quite by accident the art of cooking meat over fire—or, rather, we should probably specify, over a controlled fire.

“Welcome to the vestibule of hell.” Samuel Jones chuckled as he walked me around back of the Skylight Inn to visit the cookhouse where the pits are. There were two cookhouses, actually, cinder-block buildings the size of cottages sited at odd, arbitrary angles to both the restaurant and each other. (“Granddaddy apparently hired a drunk to design everything out here,” Samuel explained.) The larger of the two buildings had recently been completely rebuilt, having burned to the ground late one night after one of its brick hearths had failed. “We keep those fires burning twenty-four/seven, and every couple of years even the firebricks lining the inside of the chimneys just give out.” He shrugged. “I’d say this cookhouse has caught on fire about a dozen times. But that’s just how it goes when you’re doing whole-hog barbecue the right way.”

Sometimes it’s the hog grease that pools in the bottom of the pit that catches fire; other times a burning cinder will climb the column of smoke rising through the chimney and then fall back onto the roof. Just the other night, Samuel happened to be driving by the restaurant a couple of hours after closing time when he noticed a tongue of flame licking out from beneath the smoke-room door. “Now, that was a real close call,” he smiled. (A surveillance camera in the cookhouse indicated the fire had started only four minutes after the pitman had left for the night.)

Charles Lamb would no doubt be pleased to know that there are still men in North Carolina upholding the tradition of burning down whole buildings in order to improve the flavor of pigs.

Samuel is a cheery, round-faced, goateed man of twenty-nine who has been working in the family business off and on since he was nine years old. He is abundantly proud of the institution his family has built, and feels a profound sense of obligation to keep the tradition not just going but uncontaminated by modern innovations, aka “shortcuts.” Southern barbecue is ever looking only backward, but over time that gets harder and harder to do. “It’s a fact that our family cannot ever sell this business,” he explains, perhaps a bit ruefully, “because, see, we’re grandfathered in. With the health department. Anyone who bought it who wasn’t a Jones? Well, they would have to bring the place up to code, and right there, that would be the end of it.”

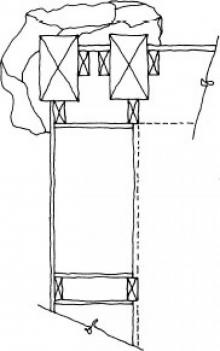

As we stepped into the new cookhouse, I could immediately see what he meant. Actually, I couldn’t see much of anything at first: The room was wreathed in a thick fog of fragrant wood smoke, and though it couldn’t have been more than twenty-five feet from one end of the building to the other, I could barely make out the steel door on the far wall. At either end of the room stands a big, deep brick fireplace, in which a monster-sized grate fabricated from car axles holds a tall stack of flaming logs. Bright-orange cinders drop between the axles, where they’re scooped out with a shovel and then fed into the pits. The pits line both of the long walls: a sarcophagus of brick, maybe three feet tall, with iron bars running across them to hold up the hogs and, suspended above each of them by cables, a four-by-eight sheet of black steel, hinged and counterweighted with cinder blocks, to cover them. The pits can hold as many as a dozen two-hundred-pound hogs at a time. On the insides, the pits are caked with an oily black grime that would definitely horrify a health inspector, except perhaps a North Carolina health inspector. It seems that the state has instituted a special, more lenient health code for barbecue establishments; that, and the informal grandfather clause to which Samuel had alluded, is all that stands between a place like this and condemnation.

“Yeah, we clean the pits now and then, depending,” Samuel offered when I broached the sanitation issue. “But you don’t want to clean them the whole way out, because then you’re losing all that good insulation.” The problem is, that cake of grime, which a chemist would probably say consists of equal parts saturated pig fat and the particulate matter suspended in wood smoke, is highly flammable. So, it seems, is the smoke we were breathing, which, to my alarm, Samuel claimed could actually ignite if it got sufficiently thick and the room sufficiently hot. “That’s called a flash-over,” he offered. Samuel has become, perforce, a close if not always entirely successful student of fire. He mentioned he’d joined the Ayden Volunteer Fire Department. Under the circumstances, this would seem like the politic thing to do.

The vestibule of hell: The pit room was in fact an infernal chamber, and not a place likely to stimulate an appetite for cooked pig in many people. The residues of fires big and small were everywhere, blackening the bricks, charring the ceiling, puckering the plywood walls. While Samuel and I talked, I could see over his left shoulder a spectral presence emerging out of the smoke, the figure of a slightly bent black man slowly pushing a wheelbarrow topped with a sheet of bloodstained plywood on which the splayed pink carcass of a hog precariously balanced. I could see the hog’s eyeless head, bobbing slightly on the lip of the wheelbarrow, and, as it drew closer, the face of

the man carefully inching it forward. It was deeply lined, leathery, and missing several teeth.

Samuel introduced me to James Henry Howell, the Skylight Inn’s longtime pit master. Howell made it instantly clear he would be leaving all the talking to the Joneses. He had work to do, and indeed it appeared that the lion’s share of the physical labor performed at the restaurant—putting on the hogs late in the afternoon, flipping them over first thing the next morning, carrying them, quartered, into the restaurant kitchen for the lunchtime rush, and then chopping and seasoning them on the big wooden block—was work that James Henry Howell did himself, leaving the Jones men free to hold forth. Which was fine by me, except it meant I probably wouldn’t be getting any hands-on experience or how-to instruction here in Ayden. That was going to have to wait.

Back and forth across the pit room Mr. Howell slowly wheeled his hogs, melting into the haze to fetch another carcass from the walk-in cooler, then emerging again with his load, which he would tenderly tip onto the iron grates. Howell worked slowly and deliberately, and when he was done putting the hogs on, he had created an arresting tableau: a smoke-dimmed conga line of splayed pink carcasses, laid out skin side up and snout to butt. The interior of the cookhouse now looked like a bunkroom, the sleeping hogs bedded down for the night. Of all the animals we eat, none resembles us more closely than the hog. Each the size of a grown man, hairless and pink, its mouth set in what looks very much like a sly smile, the half dozen pigs laid out in this smoky crypt made me think of many things, but definitely not lunch or dinner.

It was difficult to regard this pit room, filthy and littered with cinders, as a kitchen, but of course that is what it is. And that is why the state of North Carolina has been forced to choose between the equitable enforcement of its health codes and the survival of whole-hog barbecue. Sacred local tradition that it is, barbecue has won, at least for the time being. But this is a most unusual kitchen, one where the principal cooking implements are wheelbarrows and shovels, and the pantry, such as it is, contains nothing but hogs, firewood, and salt. In fact, the entire building is a kind of cooking implement, as Samuel explained: We were inside a giant low-temperature oven for the gentle smoking of pigs. Just how tightly the cookhouse is sealed—even the pitch of its roof—all influence the way the meat cooks.

After the hogs are on, Howell begins shoveling wood coals underneath them, transferring the smoldering cinders, one spade-full at a time, from the hearths, now glowing a deep red, across the room to the pits. Carefully pouring the incandescent coals between the iron bars, he arranges a line of fire roughly around the perimeter of each hog, a bit like the chalk line silhouetting the body at a crime scene. He puts more coals at the ends than in the middle, to compensate for the fact that the different parts of the hog cook at different rates. “That’s just one of the challenges of whole-hog cooking,” Samuel explained. “Cooking just shoulders, like they do over in Lexington, now, that’s a whole lot easier to control.” Samuel snorts the word “shoulders” derisively, as if cooking pork shoulders was like throwing frankfurters on the grill. “’Course, that’s not barbecue in our view.”

After he’s arranged the coals to his satisfaction, Howell splashes water on the backs of the hogs and sprinkles a few generous handfuls of kosher salt—not to flavor it, Samuel said, but to dry out the skin and encourage it to blister, thereby helping to effect its transubstantiation into crackling.

It is a long, laborious way to cook. Mr. Howell will shovel a few more coals around the drip line of each pig every half hour or so until he leaves for the evening at six. Several hours later, around midnight, co-owner Jeff Jones, whom everyone seems to call Uncle Jeff, will have to stop back in to check if the pigs need any more heat on them. The idea behind the line of perimeter fire is to build a lasting, indirect source of heat, so that the hogs cook as slowly as possible through the night. Yet at the same time you want those coals close enough to the pig’s drip line so that when its back fat begins to render, some of it will have some nice hot coals on which to drip. The sizzle of those drippings sends up a different, meatier kind of smoke, which adds another layer of flavor to the pork. It also perfumes the air in a way that a wood fire alone does not.

That perfume is what I could smell from the road, and what I was beginning to smell again. Even now, standing here in the middle of this sepulchral chamber slightly starved for oxygen, hemmed between these two serried ranks of the porky dead, I was more than a little surprised to register somewhere deep in my belly the first stirrings of … an appetite!

It is a powerful thing, the scent of meat roasting on an open fire, which is to say the smell of wood smoke combined with burning animal fat. We humans are strongly drawn to it. I’ve had the neighbor’s children drift over “for a closer smell” when I’ve roasted a pork shoulder on the fire pit in the front yard. Another time, a six-year-old dinner guest positioned himself downwind of the same cook fire, stretched out his arms like an orchestra conductor, and inhaled deeply of the meaty-woody perfume, once, twice, and then abruptly stopped himself, explaining that “I’d better not fill up on smoke!”

Apparently the same perfume is equally pleasing to the gods, whose portion of the animals we sacrifice to them has traditionally been not the flesh of these animals but their smoke. There are two good reasons for this. Humans must eat to survive, but gods, being immortal, have no such animal needs. (If they did, they would also need to digest and then, well, eliminate, which doesn’t seem terribly godlike.) No, the idea of meat, the smoky, ethereal trace of animal flesh wafting up to heaven, is what the gods want from us. They can and do fill up on smoke. And besides, if the gods did demand cuts, how would we ever get their portion of meat to them? The fragrant column of smoke, symbolizing the link between heaven and earth, is the only conceivable medium of conveyance, and also communication, between humans and their gods. So to say this aroma is divine is more than an empty expression.

People have known that the smoke of roasting meat is pleasing to the gods at least since the time of Genesis, where we learn of several momentous sacrifices that altered man’s relationship to God and disclosed divine preferences. The first such sacrifice was actually two: the offerings of Cain and Abel. Cain, a tiller of the fields, sacrificed a portion of his crop to Yahweh, and Abel, a shepherd, a choice animal from his flock—and God made it clear it was the sacrifice of domestic quadrupeds he prefers.* The next momentous sacrifice came after the waters of the Flood receded, when Noah, back on dry land at last, made a “burnt offering” to Yahweh. This is a type of sacrifice in which the entire animal is burned to a crisp—i.e., turned to smoke, and thereby offered to God. “And the Lord smelled a sweet savour; and the Lord said in his heart, I will not again curse the ground any more for man’s sake … neither will I again smite any more every thing living, as I have done.” (Genesis 8:21) If there was ever any doubt about the efficacy of animal sacrifice (not to mention the sheer power of scent), Noah’s experience should have put it to rest: The aroma of burning meat is so pleasing to God that it tempered his wrath and moved him to take the option of worldwide doom completely off the table for all time.

It’s striking how many different cultures at so many different times have practiced some form of animal sacrifice involving the roasting of meat over a fire, and just how many of these rituals conceived of the smoke from these cook fires as a medium of communication between humans and gods. Anthropologists tell us some such practice is very nearly universal in traditional cultures; indeed, you might say it is the absence of such a ritual in our own culture that is probably the greater anomaly. Though it may be that the faded outlines of such rituals can still be glimpsed in something like whole-hog barbecue.<

br />

But the prominence of smoke in rituals of animal sacrifice suggests we need to add another myth of the origins of cooking to our growing pile: Maybe cookery begins with ritual sacrifice, since putting meat on a fire solves for the problem of how exactly to deliver the sacrificial animals to their heavenly recipients.

What the gods have demanded from us in terms of sacrifice has gotten progressively less onerous over time. So what started out as a solemn, psychologically traumatic ritual eventually evolved into a ceremonial feast. Human sacrifice gave way to animal sacrifice, which in turn gave way to partial animal sacrifice in a happy series of dilutions culminating (or petering out) in the modern backyard barbecue, where the religious element is, if not completely absent, then pretty well muffled. It’s not a big conceptual leap to go from the observation that the gods seem perfectly happy with a meal of smoke to realizing that maybe we don’t have to incinerate the whole animal in a burnt offering in order to satisfy them. The gods can enjoy the smoke of the roasting animal, and we can enjoy the meat. How convenient!

But keeping the best cuts of sacrificial animals for human consumption is an innovation hard won, at least in classical mythology, and the figure responsible for it paid a heavy personal price. The Prometheus legend is usually read as a story about man’s hubris in challenging the gods, the theft of fire representing the human assumption of divine prerogative—costly yet a great boon to civilization. All this is true enough, but in the original telling, by Hesiod, the story is a little different. Here, it turns out to be as much about the theft of meat as it is about the theft of fire.

A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder

A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation

Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation The Omnivore's Dilemma

The Omnivore's Dilemma How to Change Your Mind

How to Change Your Mind Food Rules

Food Rules In Defense of Food

In Defense of Food A Place of My Own

A Place of My Own