- Home

- Michael Pollan

A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder Page 13

A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder Read online

Page 13

We walked out to the site, where I showed him Charlie’s sketches for the building as well as the footing detail. He studied the drawings for a minute or two, made the obligatory carpenter’s crack about architects (“ivory tower,” etc.), and then said what he always says any time you ask him if he might be interested in a project:

“Piece a cake.”

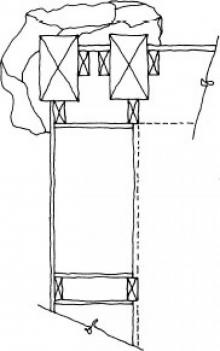

We settled on an hourly rate and agreed to get started as soon as I had my building permit and the holes for the footing could be dug. Originally I had planned on digging them myself, but a backhoe was going to be on the property later in the month (to repair the pond; it’s a long story), so I’d figured I might as well have the excavator do it. Digging a half-dozen four-foot-deep holes in this ground by hand was a job I was happy to skip; it’s one thing to honor the rocks around here, and quite another to confront them at the end of a spade. Before he took off, Joe offered to give me a hand staking out each of the six holes to be dug—one at each of the building’s corners and then a pair in the middle of the rectangle, where the building would step down with the grade of the site.

Charlie and I had already staked two of the corners over the July Fourth weekend, deciding on the building’s precise location with respect to the rock (crouching a few steps back so as not to upstage it) as well as its orientation to the sun. Joe asked me how we’d determined the precise angle. It hadn’t been easy. The obvious solution would have been to adopt the orientation of the small clearing alongside the boulder, which ran more or less due east to west. But that angle would have admitted too much direct sunlight through the front window of the building, even with its visor, particularly on spring and autumn afternoons. Due west also put the big ash tree directly in my line of sight, which promised to block the sense of prospect from the desk.

So Charlie and I had experimented, the two of us standing side by side where the front window would be, facing dead straight ahead and revolving our bodies in a stiff, incremental pirouette, one of us occasionally leaving the front line to check the view from another imaginary window. As we pivoted the building on its axis, each ten-degree shift in angle caused a revolution in perspective from every window. We would nudge the front of the building into a winning prospect only to find that the south-facing casement window now stared out at a Ford Pinto up on blocks in my neighbor’s yard. This must have gone on for an hour or more, both of us reluctant to give up without testing every conceivable angle. We were planting the building, after all, determining what was going to be my angle on things for a long time to come. Finally we hit upon one that seemed to satisfy all the windows and avoid a too-direct confrontation with the ash or the afternoon sun. By the compass, my angle on things was going to be 255 degrees, or 15 degrees south of due west.

Now Joe and I made preparations to fix this perspective in concrete. Once we had planted the four corner stakes, making sure they formed a rectangle of the dimensions specified on Charlie’s footing plan (14?2? by 8?9?), we checked to make sure it was square by measuring the diagonals; if the lengths of the two diagonals were equal, that meant the rectangle was square. This may have been the first time in my life I had successfully applied an axiom learned in high school geometry. Though I didn’t fully appreciate it at the time, I was opening a chapter in my life in which the rules of geometry would loom as large as the rules of grammar ordinarily do. It seemed like a snap, too, but then I still had no idea how much less forgiving the new rules could be.

Now we had a life-size diagram of the building, outlined on the ground in yellow nylon string, and the effect of it, on the site but also on my spirits, was larger than I might have guessed. Part of it, I suppose, was the sense of satisfaction that often comes from making a straight line in nature—whether in a row of seedlings, a garden path, or a baseball diamond. “Geometry is man’s language,” Le Corbusier used to say, and it was cheering to see this perfect rectangle take shape on the rough, unreliable ground. (Who knows, but the fact that the rectangle’s proportions chimed with the Golden Section might have had something to do with it too.) All our abstract drawings on paper were at last being transferred to the real world.

While I stood there admiring the view from inside my box of string, Joe had been sitting up on top of the big rock, studying Charlie’s footing plan. He had been uncommonly quiet up to now, merely nodding as I explained to him the thinking behind the various decisions Charlie and I had made, and I had taken his silence for consensus. More likely, he’d been doing his best not to second-guess us, because now he interrupted my reverie with a question.

“Do you really want to put fir posts directly on top of a rock?”

I didn’t see why not.

“In one word? Rot.”

He explained that the end grain of the posts would wick up moisture from the boulders they sat on, a bad enough situation made worse by the fact that, among woods, fir offers relatively little resistance to rot.

“My building, I’d do it differently. But it’s up to you.”

“It’s up to you” just might be the single most irritating thing you can say to somebody under the circumstances, a cranky parody of the liberty it pretends to bestow. But I decided to keep a lid on my annoyance.

“So how do you suggest we do it?”

“Couple of options,” he began, settling a little too quickly into the role of tutor, his laconic manner of a few moments ago now a memory. I was treated to a detailed lecture about the virtues and drawbacks of pressure-treated lumber (wood that has been immersed under pressure in a solution of chemicals, including arsenic and copper, to kill off the microorganisms that dine on wood). This was followed by a disquisition on the relative weather-resistance of a dozen different tree species, beginning with pine (highly vulnerable) and ending with locust, which is so hard and rot resistant that it can be sunk naked into the ground. Redwood or cedar would apparently last much longer than fir, though both were considerably more expensive. Finally, Joe ran through a list of the various wood preservatives and sealants on the market, things we could apply to the end grain if I decided to stick with fir.

Everything Joe was saying sounded sensible, but I told him I wanted to consult with Charlie before making a decision. This was the wrong thing to say. I should simply have said I wanted to think it over. Invoking Charlie’s authority clearly annoyed Joe, who evidently had already concluded that Charlie was just another ivory-tower architect with his head in the clouds, if not someplace worse. Joe works hard at seeming to take things in stride, however. He maintains a whole vocabulary of phrases to indicate how non-chalant he is—“piece a cake,” “cool,” “I’m easy,” “no problem,” “no sweat”—as well as some novel contractions of these, one of which he now produced, along with a slightly offended, suit-yourself hike of the shoulders:

“Cake.”

Joe’s monosyllabic shrug masked strong feelings, and immediately I could see that this construction project was not going to escape the edginess that traditionally crops up between architects and builders, a complicated set of tensions rooted in real differences of outlook and interest and, inevitably, social class. On building sites all over the world, architects are figures of ridicule, their designs derided for their oddness or impracticality and their construction drawings, which on a job site are supposed to have the force of law, dismissed as cartoons or “funny papers.” What remained to be seen on this particular site, however, was exactly where I fit into this drama, since I was both client (traditionally an ally of the architect) and builder. The fact that I would be working on this project, and not just paying for it, changed everything. I was the patron of Charlie’s fancy ideas, but I also faced the practical problem of making them work, something I probably couldn’t manage without Joe’s help. Among other things, Joe was poking around to see whose authority I was placing first.

And I wasn’t sure. Joe had shifted the ground on me a bit, which is why I hoped to table for the time being the issue of how our fir posts would meet their rock feet. I’d always regarded Charlie as

a realist among architects, somebody with his own feet planted firmly in the world, and an authority on practical questions. His footing detail may have gotten a little baroque, but that was only because its romance of the ground had been tempered by what seemed like some hardheaded realism about it—hence the four feet of concrete and the steel rods. What could possibly be more down-to-earth than that footing drawing?

But if Joe was right, he had spotted what appeared to be the Achilles’ heel of Charlie’s footing detail. It wasn’t a problem we had to solve right away—whatever we did about it, the concrete piers first had to be poured, the boulders drilled and pinned. Touchy though he might be at times, I felt relieved to know Joe would be along on what promised to be a treacherous voyage to the material underworld. I’d found my prickly Virgil.

A few weeks later I paid a visit to Bill Jenks, the local building inspector. Though Charlie hadn’t quite finished the construction drawings, with his rough sketches and the footing plan I could apply for the building permit I would need before Joe and I could pour the footings. On any construction project, the building inspector is a slightly intimidating figure, since he wields the power to order expensive changes in a design or force a builder to redo any work that isn’t “up to code.” He is the final authority—the building trade’s judge, superego, and reality principle rolled into one—and he holds the power to condemn any building that doesn’t meet his approval. I once asked a contractor whom he appealed to when there was a difference of opinion with the building inspector. The fellow squinted at me for the longest time, trying to determine if I could possibly be serious. He’d never heard of anyone questioning a ruling from the building inspector. But surely there must be some court of appeal, I insisted. What about due process? The Fourteenth Amendment? “I suppose you could appeal to the governor,” he offered after long reflection. “Weicker might be able to overrule Jenks.”

“Code” consists of a few thousand rules, most of them commonsensical (the minimum dimension of a doorway, for example: 2?4?) but many others obscure and seemingly picayune (the maximum number of gallons of water in a toilet tank: 1.6). The house that satisfies every jot and tittle of the building code probably hasn’t been built yet, which is why a building inspector is given wide latitude in the exercise of his judgments. He has the authority to sign off on minor transgressions. Or he can go strictly by the book. Most of the contractors I’ve met live in constant low-grade terror of the building inspector.

You might think that, since the building inspector’s mission in life is to look out for the interests of the consumer, who on this particular job happened to be me, Jenks could in this instance be expected to go fairly easy. In the days before my interview with him, the approach of which instilled in me a moderate but unshakable level of dread, I’d taken no small comfort in this theory. But when I tried it out on Joe, the night before my meeting, he said I could forget it. The building inspector is paid to take a very, very long view, Joe explained. He’s thinking about hundred-year storms (the worst storm to hit a region in a century, a conventional standard for structural strength) and about the persons yet unborn who will own and occupy my hut in the next century.

My first impression of Jenks did little to relieve my anxiety. Actually, it wasn’t an impression of Jenks himself, but of his boots, which stood rigidly at attention outside the door to his office. They were knee-high black riding boots, easily a size thirteen, that had been arrayed with military precision and buffed to a parade-ground sheen. The boots said two things to me, neither of them reassuring. First, any man who would wear them was without a doubt drunk with power, very possibly a closet sadist or a collector of Nazi paraphernalia. Second, such a person had a serious fetish for meticulousness: You could shave in the shine on these boots, they butted the wall at ninety degrees dead on, and the space between them appeared to have been microcalibrated.

These were the boots of the man who would be judging my craftsmanship each step of the way.

Fortunately, the man himself wasn’t quite as intimidating as his footwear, though he certainly took his sweet time looking over the drawings I spread out across his drafting table. Jenks was slender and tall, perhaps six foot two, though his posture made him seem considerably taller: The man was plumb. Picture a two-by-four with a handlebar mustache. For a long time Jenks said nothing, just stood there smoothing down the ends of his great black handlebars as he walked his eyes over every inch of Charlie’s drawings.

“Looks to be sturdy enough,” he announced at last. I took this as a compliment, until I realized he was making fun of the beefy four-by fir timbers Charlie had spec’d for the frame, which were substantially more substantial than a one-story outbuilding required. “See a lot of tornadoes out your way?” I laughed, largely, and it seemed as though everything was going to be all right. Which it was, until he got to the footing detail and stopped. He began tapping the drawing with his pencil eraser, lightly at first, then much harder and faster. “Nope. I won’t approve this as drawn. Any framing within eight inches of the ground must be pressure-treated, and that includes the posts sitting on these rocks.” Joe had been right; the footing was indeed my hut’s Achilles’ heel.

But Jenks was willing to give me the building permit anyway, provided I signed a piece of paper promising to make the changes he specified. He instructed me to call for a field inspection as soon as we’d poured the footing, then again when the framing was complete. I left his office feeling buoyant, official, launched at last. When I got home I walked out to the site and nailed the bright yellow cardboard building permit to a tree. The following morning, we would pour.

Concrete is peculiar stuff, so accommodating one moment, so adamant the next. Not that it’s the least bit mercurial—few things in this world are as reliable as concrete. Wet, it can be counted on to do almost anything you want; it’s as happy taking its formal cues from a mold as it is acceding to gravity. Vertical, horizontal, square or curved, ovoid or triangular, concrete can be made to do it all, no complaints. Once cured, however, the stuff’s incorrigible, as stubborn and implacable as rock. What was feckless is now transcendently determined, and all but immortal. In the case of concrete, there’s no turning back, no melting it down to try again, as plastic or metal permits, no cutting it to fit, like wood. Here in a handful of cold gray glop is the irreversible arrow of time, history’s objective correlative. A fresh batch of concrete can pass into the future along an almost infinite number of paths—as road, bridge, pier, sculpture, building, or bench—but once a path is taken, it is as one-way and fixed as fate. Right here is where the two meanings of the word “concrete”—the thing and the quality—intersect: for what else in the world is more particular?

These are the kinds of thoughts working with concrete inspires, on a suitably gray and chilly November afternoon. Although one or two steps in the process are critical, for the most part mixing and pouring concrete doesn’t fully engage the intellect, leaving plenty of room for daydream or reflection. Mainly it’s your back that’s engaged, hauling the eighty-pound sacks of ready-mix to the site, pouring them into a wheelbarrow along with twelve quarts of water per bag, and then mixing the stiff, bulky batter with a rake until it’s entirely free of lumps. The stuff is very much like a cake mix, in fact, except that each batch weighs more than three hundred pounds (three bags plus nine gallons of water) and licking the fork is not a temptation. You can make concrete from scratch too, mixing the gravel, sand, and Portland cement (a powder fine as flour) according to the standard recipe (roughly, 3:2:1 for a foundation), but for a job this size Joe had recommended ready-mix, the Betty Crocker of concrete.

Pliny wrote somewhere that apples were the heaviest of all things. I don’t know about that. It’s my impression that eighty pounds of concrete weighs a good deal more than eighty pounds of almost anything else, apples included. Apples at least show some inclination toward movement—they will roll, given half a chance—whereas a bag of concrete lying on the ground very much wants to stay

there. Add water, and the resultant mud is so thick and heavy—so stubbornly inert—that dragging a tool through it even once is a project. I would plunge my rake head down into the mire and then pull at it with all the strength I could summon, which yielded maybe six or seven inches of movement, copious grunts, and an almost exquisite frustration at the sheer indifference of matter at rest. Hats off, I thought, to the Mafia capo who first perceived the unique possibilities for horror in sinking a man’s feet in cement. For Joe the stuff behaved a good deal more like cake batter, however, and whenever my stirring grew so lugubrious that the concrete threatened to set, he would take the rake from me and, throwing his powerful back and shoulders into the work, whip the concrete smooth as if with a wire whisk.

For forms we were using sonotubes, which are nothing more than thick cardboard cylinders—stiffened, oversize toilet paper rolls sunk into the earth. Whenever Joe judged a batch of concrete “good to go,” the two of us would shoulder the wheelbarrow into position, tip it down toward the lip of the sonotube and then, with a shovel, herd the cold gray slurry into the cylinder. It would land four feet down at the bottom of the shaft with a sequence of satisfying plops. The sonotubes were cavernous—fourteen inches in diameter, broad enough to give our boulders a nice, comfortable seat—and it took almost two barrow loads to fill each one. But by the end of the day all six had been filled—more than a ton of concrete mixed and poured by hand. Then with a hacksaw we cut lengths of threaded steel rod and inserted them in the center of each concrete cylinder. We bent the submerged end of each rod to improve its purchase on the concrete and then left about eight inches exposed above the top of the pier; to this pin we would bolt our boulders.

A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder

A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation

Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation The Omnivore's Dilemma

The Omnivore's Dilemma How to Change Your Mind

How to Change Your Mind Food Rules

Food Rules In Defense of Food

In Defense of Food A Place of My Own

A Place of My Own